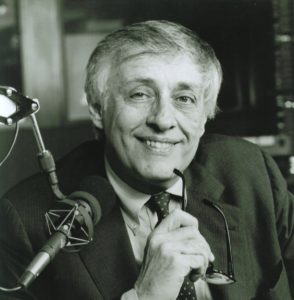

Milt Rosenberg: 1925 – 2018

On January 19, 2018, Milt’s family held a well-attended memorial service for him, at Bond Chapel on the University of Chicago campus. Here’s an abridged version of remarks by his son, Matt Rosenberg.

On January 19, 2018, Milt’s family held a well-attended memorial service for him, at Bond Chapel on the University of Chicago campus. Here’s an abridged version of remarks by his son, Matt Rosenberg.

We’re gathered here today today to remember and celebrate the rich life of my father, Dr. Milton J. Rosenberg. He was a professor of social psychology at the University of Chicago, and for 38 years the host of a talk radio show like no other, Extension 720 on WGN-AM in Chicago.

Before getting started, I’d like to pay respect to some of Milt’s survivors. They include his wife Marjorie, who is in a care facility in Seattle and not able to attend. She loved Milt deeply. He was the light of her life. Theirs was a meeting and melding of the minds, for the ages. A number of those in attendance here today will remember dinner conversations with Milt and Marjorie, that flowed, and flowed.

My father is also survived by his grandchildren Max and Ava, and his remarkable daughter-in-law, my loving wife Patricia. Survivors also include Milt’s brother Norman, an internationally regarded climatologist, as well as his sister-in-law Sarah, and Norman and Sarah’s children: my cousins Daniel and Lisa.

Right now, I’d like to kick off this service with a few memories of my father.

***

When I was growing up in Chicago in the 1960s and 70s, my dad was my personal concierge to the city and to history in the making.

In 1968 when I was 10, Milt and Marjorie forcibly recruited me into the Eugene McCarthy for President Campaign. I was parked in a basement office in Harper Court in Hyde Park, stuffing envelopes for mailers intended to help the silver-tongued senator from Minnesota become the party’s nominee. One day we joined about 10,000 other people at Midway airport when the candidate came to town for the Democratic National Convention. It was electric.

Milt took me one night to Chicago’s Lincoln Park on a sort of sociological field trip. It was filled with anti-war protestors in town for the convention. They were camped out in tents, by the thousands. It was like Woodstock – but minus the electric guitars, and a whole lot edgier. I still remember the “undercover” police leaning on their gun-metal grey Dodge sedan, parked on the grass, dressed in brown polyester, and surveying the landscape. They looked nervous, and outmatched. A day or two later Chicago’s uniformed police, acting on orders from the mayor, violently beat protestors outside the Conrad Hilton when “the whole world was watching” on TV.

I understood the news, and that watershed era better because my father had given me a front-row seat. He was a social psychologist in turbulent times; researching and writing about the effect of public opinion on politics and policy. He had the instincts of a good news reporter long before his career as a radio interviewer began. He knew from shoe leather.

Milt loved to explore the city. When we lived in Chicago’s South Shore neighborhood, he took me one morning for breakfast to a greasy spoon on East 71st Street. This was near the South Shore Country Club, then privately-owned, where Jews and blacks were not welcome as members. We were halfway through our pancakes and yes, bacon, when bursting through the front door of the cafe, with a whole lot of his fantastic shtick, came the world heavyweight boxing champion Muhammed Ali. Pots and pans went flying and crashing around the kitchen as Ali fixed breakfast for himself and his entourage of 10. I’ve still got his autograph.

Milt loved the movies. He took me to see what are now classic films, on first run, in Chicago theaters. Together we enjoyed and later tried to dissect the comedy Watermelon Man, with Godfrey Cambridge. It was about a stuffy white insurance executive who wakes up one morning to find out he has turned black. Milt was always hooked on good stories, and liked musicals, too. Together we saw Little Big Man, Bullitt, The Andromeda Strain, Space Odyssey, The Sound of Music, and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

Years later, our family found itself at a private reception in the White House. The canapes were just delectable. We were there because Milt – along with the musical auters of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang the Sherman Brothers, and other luminaries – were each receiving a National Medal for the Humanities. (National Endowment For The Humanities write-up for Milt’s medal).

Milt was a culinary adventurer. So going to the movies with him in downtown Chicago in the late 60s and early 70s, at places like the Michael Todd Theater, and the Chicago Theater, meant a visit to Tad’s Steaks afterward. On State Street. For $3.99 you instantly got a whopping big plateful of coronary plaque. An irresistible gristly T-bone right off the flaming grill in the window. A huge baked potato heaped with sour cream; plus salad drenched in creamy dressing, and buttery garlic bread.

Tad’s was almost as good as the polish sausages smothered with greasy grilled onions that Milt and I used to eat at the Maxwell Street Market. They were served up through the window of a mobile home trailer perched on cinder blocks. The soundtrack: live electric blues coming through amplifiers powered by automobile batteries. We relished those same Polies together at a sketchy little joint on West Madison Street just before going into the old Chicago Stadium to see the Blackhawks beat the pants off the Canadiens, Maple Leafs, or Red Wings.

But maybe we had a few too many gristly Tad’s steaks, and polish sausages – because Milt almost expired at the age of 59 in 1984. On Christmas morning that year, he suffered a major heart attack. At U of C hospitals, he had successful quadruple bypass heart surgery later the same day. Our family thanks all the doctors who for the last 33 years kept him ticking. It was more than good medicine. It was a public service.

One of the best things my father gave me was an understanding of what are the right kinds of questions to ask. He had a knack for surmounting what one of his treasured radio guests, the author and humorist Mark Steyn, has termed, “the passing frippery of the day.” Milt knew how to get to the bottom of things. And he did it in a way that left his guests and audience enlightened, and eager to learn more. It’s hard to think of a greater gift to give. Rest in Peace, my Dear Father.

Related Articles (January, 2018)